Facilitating Communities of Practice

Overview

My community of practice focused on addressing students with disabilities self-advocacy. Currently, students with disabilities are graduating high school with significantly lower college and career readiness skills due to low student self-advocacy. To be college and career ready, specifically, to access rigorous college-level coursework or demanding work environments, students with disabilities need to be able to advocate for accommodations to support their success. They also need to be aware of their disability, and the services most appropriate and necessary to increase their accessibility to various post-secondary settings. Finally, students with disabilities need to be aware of community resources and agencies available to aid them in finding employment opportunities, career development, and academic supports

This educational focus directly ties to our school’s vision and mission. The school’s vision focuses on developing student agency and equipping all students with college and career readiness skills set through an individualized holistic approach. However, current student data on students with disabilities contradicts this vision. Students with disabilities consistently and significantly trail behind their peers without disabilities both in academic achievement and students’ own perception of their college and career readiness. In both the ELA and Math SBAC scores, students with disabilities scored several percentage points away from their typical peers. In the 2019 LAUSD college and career readiness survey, 21.4% of students with disabilities met the college and career readiness standards, in comparison 40.9% of their peers without a disability. To add, the inclusive language in the vision and mission of taking a holistic approach in addressing student learning heightens the relevancy in meeting the needs of all students, including students with disabilities. Providing supports to meet academic standards, and building agency and self-advocacy in students with disabilities directly connects to the school’s vision and mission in developing students to be agents of change because it signifies students are graduating with the necessary skill set to pursue ambitious post-secondary goals.

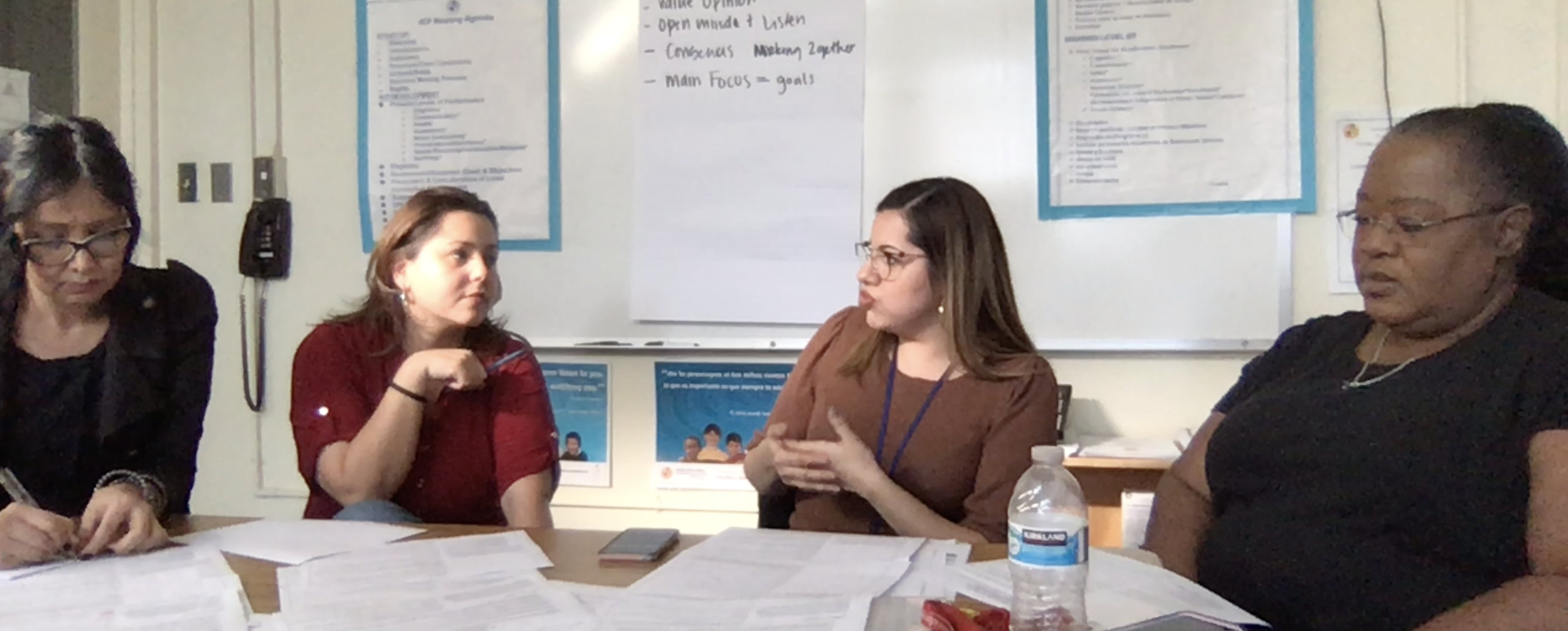

In my community of practice, each group member is a stakeholder in meeting students with disabilities needs. All of the group members have direct contact with the student subgroup. This proximity to the student population enabled commitment to fostering self-advocacy in students with disabilities. The group member has also participated in professional development precisely on building self-advocacy in students with disabilities.

Main Activities

After collaboratively reviewing school-wide data, the group identified the stark inequities among students with disabilities. Specifically, students with disabilities are graduating high school with significantly lower college and career readiness skills due to low student engagement and self-advocacy. Three sources of data-informed this problem of practice: academics, student district survey, and chronic absenteeism.

Academically, students with disabilities are not performing on academic standards needed to access rigorous coursework in a college setting. SBAC scores demonstrate an extensive gap between students with disabilities and their peers in meeting common core standards. For example, in the 2018-2019 academic school year, in the ELA SBAC, 27.77% of all students met or exceeded ELA standards, whereas 2.75% of students with disabilities met or exceeded ELA standards. In Math, 10.92% of all students met or exceeded Math standards, whereas 0.93% met or exceeded Math standards. Our team collaboratively agreed, to access rigorous college-level coursework or demanding work environments, students with disabilities need to be performing academically and advocating for academic accommodations to support their success. We also asserted the need to be aware of their disability, and the services most appropriate and necessary to increase their accessibility to rigorous academic standards. With students’ increased access to the academic standards, their performance in demonstrating their mastery of those standards will strengthen.

In a similar fashion, we observed on the college and career readiness district-wide survey, students with disabilities scored significantly lower than their peers without a disability. Questions on the survey focus on basic college and career readiness knowledge, as well as the support students, receive during high school in regards to their post-secondary options. In the 2018-2019 academic year, students with disabilities received a 21% rate on the survey in comparison to the 40.9% rate of their peers without disabilities. This data indicates many students with disabilities did not receive adequate support in high school nor do they possess sufficient knowledge to adequately navigate the post-secondary setting.

Finally, we also identified a significant gap in chronic absenteeism between students with disabilities and their peers without disabilities. In the 2018-2019 academic year, 26.7% of students with disabilities were chronically absent in comparison to 17.3% of their peers without disabilities. Students with disabilities have a higher chronically absent rate which signifies an interruption in instructional time for the students and low student engagement with the school community. Low student engagement further affects students’ academic performance, and thus, their college and career readiness.

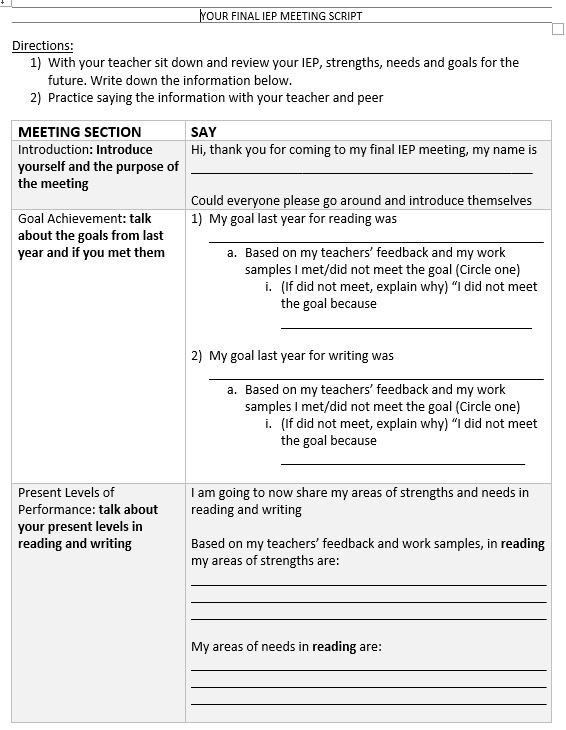

Currently, students with disabilities experience difficulty articulating their needs and the supports that would ensure their academic success. However, after the team’s collaborative analysis on strengthening students with disabilities’ self-advocacy a specific evidence-based strategy surfaced. Specifically, the team reviewed three pieces of research: Barnard-Brak & Lechtenberger (2010), Theoharis & Causton-Theoharis (2008), and Zheng, et. al (2014). The research supported the use of student-led IEP meetings as a means to directly develop or boost students’ self-advocacy skills in the secondary and post-secondary setting. The research also highlighted the positive impact this heightened self-advocacy had on the students’ academic performance.

To this effect, our group selected promoting student-led IEP meetings as our evidence-based strategy to address the problem of practice. We aimed to create protocols that would force students to reflect on their school performance and the supports they currently receive. This would require students to directly analyze their current academic performance and identify various supports they find most effective in addressing their academic needs in the classroom. If students are able to assess the supports’ effectiveness it profoundly changes their engagement with their academics because they become closely involved in evaluating their access to the curriculum

As evidenced in the research, promoting student-led IEP meetings increases self-advocacy and agency in students with disabilities. When students are required to lead their own meetings, they learn about their disability and become self-aware about their strengths and challenges. To add, through exploring their challenges they can also evaluate the supports best fit to ensure their academic success. At our planning meeting, apart from presenting our school’s data, I also provided research on fostering academic success and persistence in students with disabilities. Analysis of the research led the group to agree on pursuing a strategy centered on developing students with disabilities’ self-advocacy and self-determination. A common trend from the research also guided us to the implementation of student-led IEP meetings as a means to build student self-advocacy.

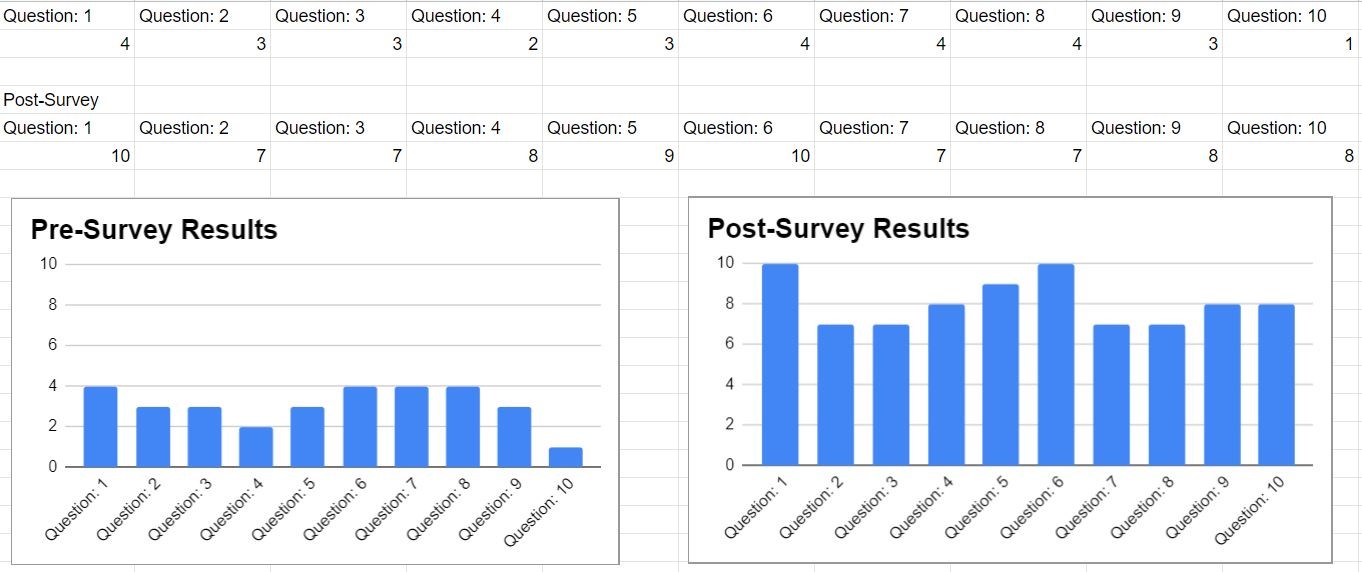

Ongoing discussion on the research and assessment of our own strategy implementation allowed our group to continue learning about establishing effective student-led IEP meetings. We met periodically to review student work and student feedback on planning for their IEP meeting. Specifically, we collected data on students’ understanding of their academic success, academic needs, appropriate accommodations, and post-secondary options. This data primarily stemmed from pre and post-surveys after walking students through student-led IEP meeting protocols in preparation for their student-led IEP meeting.

The group conducted pre and post-surveys with the students. The pre-survey served to gauge students’ current understanding of their academic strengths, academic needs, and knowledge of the appropriate accommodation and community resources. The post-survey measured the growth in self-awareness once students walk through their IEP data and disability-specific information needed for them to lead a student-led IEP meeting. The pre-survey informed the protocol we created, in order to guide our students in reviewing and evaluating their current academic levels. While the post-survey primarily served to refine the protocol and inform any necessary adjustments or scaffolds in preparation for their IEP meeting where they will present the information.

Reflection

An area of strength in co-facilitating a community of practice is my ability to solicit and consider diverse viewpoints and opinions. I ensured it was a collaborative process by prompting my team members to jointly review student data, student learning, and research to build consensus on the appropriate evidence-based strategy to implement. In addition, at various parts in our learning process, I consistently encouraged my team members to give their opinion on how to proceed in implementing the next steps in our evidence-based strategy.

An area of growth would be to develop a meeting protocol to ensure our meetings always returned to student learning and student needs. This would enable our meetings to be more efficient in reaching a consensus and grounding our next steps on student needs. Although my team adjusted the implementation of our strategy at various points, perhaps utilizing a meeting protocol would also allow us to consider the students who did not reach our desired impact. Specifically, the protocol could have encouraged a discussion on how to support individual students.

References

Barnard-Brak, L. & Lechtenberger, D. (2010) Student IEP Participation and

Academic Achievement Across Time. Remedial and Special Education, 31(5), 343-349.

Theoharis, G. & Causton-Theoharis, J. N. (2008) Oppressors or Emancipators:

Critical Dispositions for Preparing Inclusive School Leaders. Equity & Excellence in Education, 41(2), 230-246.

Zheng, C., Gaumer Erickson, A., Kingston, N., & Noonan, P. (2014) The Relationship

Among Self-Determination, Self-Concept, and Academic Achievement for Students with Learning Disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 47(5), 462-474.

Standards

|

CAPEs

|

DESCRIPTION

|

EVIDENCE

|

|

1B

|

Developing a Shared Vision and Community Commitment

|

- The leadership team analyzed available student and school data from multiple sources to increase students with disabilities’ college and career readiness.

- The leadership team developed a student-centered project on supporting teaching and learning for students with disabilities to increase their academic success and align student performance to our school’s vision and mission.

- The leadership team communicated the project centered on college and career readiness to the staff through Special Education department meetings.

|

|

1C

|

Implementing the Vision

|

- The leadership team engaged stakeholders in sharing data to assess program/instructional strengths and needs to promote an increase in students with disabilities college and career readiness, such as the implementation of the student-led IEP meeting template.

- The leadership team collected and analyzed multiple sources of data for ongoing monitoring to determine if the project was moving towards the school’s vision of increasing students’ college and career readiness, such as the using data from student surveys.

|

|

2A

|

Personal and Professional Learning

|

- I was inclusive in helping my team members identify areas of professional strengths and development in working to improve instruction and student learning for students with disabilities.

- The leadership team used research to support evidence-based practices, such as student-led IEP meetings to promote college and career readiness for students with disabilities.

|

|

2B

|

Promoting Effective Curriculum, Instruction, and Assessment

|

- I used a range of communication approaches, such as whole group presentations or individual conferences to assist staff and stakeholders in understanding student assessment processes, and how these processes relate to accomplishing the school’s vision and goals.

- With my leadership team, we identified and used multiple types of evidence-based assessment measures and processes, such as student surveys and SBAC scores, to determine student academic growth and success.

|

|

2C

|

Supporting Teachers to Improve Practice

|

- With my leadership team, I used sociocultural theory to design and facilitate various strategies that guided and supported my team members in improving their practice through contextualized learning and participation.

- I built a comprehensive and coherent system of professional learning by establishing and adhering to meeting norms, which focused our efforts in reaching the shared vision of equitable access to learning opportunities and resources, and positive outcomes for students with disabilities.

|

|

2D

|

Feedback on Instruction

|

- I used reflective conversations and collegial feedback with my team to guide our targeted instructional improvement centered on increasing students with disabilities college and career readiness.

|

|

3C

|

Managing the School Budget and Personnel

|

- I worked with my leadership team to provide staff with unbiased, evidence-based feedback about implementing student-led IEP meetings to improve instructional practices, and foster positive learning environments.

- Provided my leadership team with constructive suggestions about strategies, available resources, and technologies that support students with disabilities learning, safety, and well-being.

|

|

5A

|

Reflective Practice

|

- At every leadership meeting, I maintained a high standard of professionalism, ethics, integrity, justice, and equity and expected the same behavior of others by collectively establishing group norms and consistently adhering to those group norms.

|

|

5B

|

Ethical Decision-Making

|

- In conducting a root-cause analysis with my leadership team on students with disabilities low college and career readiness, we were able to recognize any possible institutional barriers to student and staff learning and use strategies to overcome those barriers.

- During meetings. I guided staff to examine issues that affect students with disabilities' performance in accomplishing the school’s vision and mission centered on college and career readiness.

|

|

5C

|

Ethical Action

|

- At every leadership team meeting, I acted with integrity, fairness, and justice, and intervened appropriately by remaining collaborative and open to considering diverse opinions, so that all members were treated equitably and with dignity and respect.

|